Mana Contemporary, Jersey City, NJ

Mana Contemporary is an arts center with three locations: Chicago, Miami and Jersey City. Each location has exhibition space and also houses artists studios. These photos are from the Jersey City location. Like so many contemporary art museums it is housed in a old industrial building.

It is not the easiest place to visit. It is only open for four hours, one day a week (Saturday) and it’s not easy to find. Bring the exact address and check out the picture of the building because there are no signs and the entrance doesn’t face the street. It has a parking lot (a big deal in Jersey City), admission is free and you’ll see some great art.

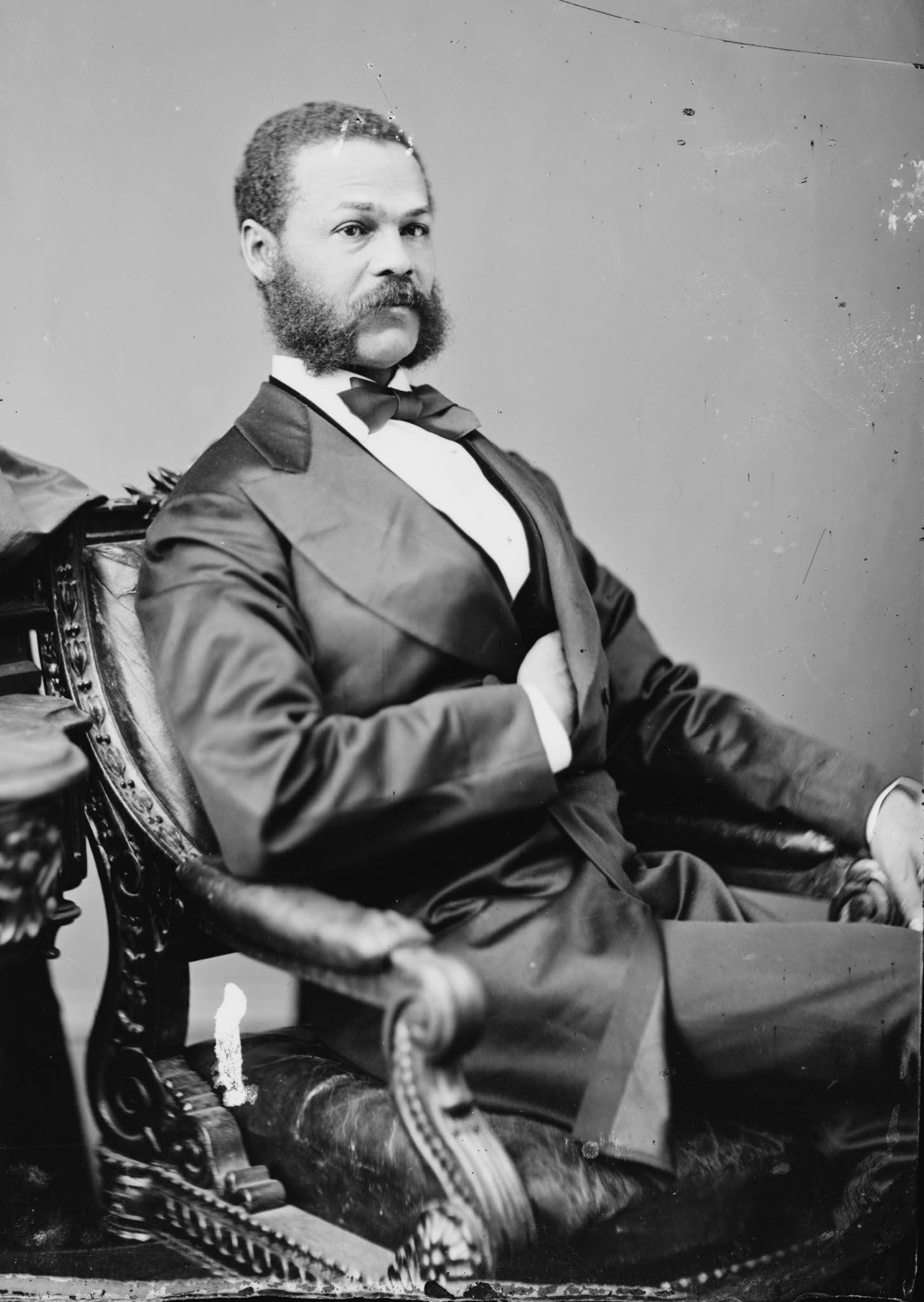

Josiah Thomas Walls was used to dodging bullets. He did it as an active Civil War veteran. He dodged an assassin’s bullet while campaigning to represent Florida in Congress. And once elected, he dodged the bullet thrown at him by a House committee that unseated him only to be re-elected twice.

Walls was the first Black representative elected in Florida and he remained the only one until the 1990’s.

He was born a slave in 1842 in Winchester, Va. His owner, Dr. John Walls, was likely his father. When the Civil War broke out he was conscripted to work as a servant in the Confederate Army. He was captured by Union soldiers in 1862 and emancipated. A year later he was serving in the Union army, a member of the United States Colored Troops. His service landed him in northern Florida where he remained after the war.

Walls was to serve three terms in Congress between 1871 and 1877. He was active and well-respected as a legislator. The New National Era, an African-American newspaper based in Washington, had this to say about Walls (Feb. 5, 1874):

“While active and earnest in behalf of the Civil Rights Bill and measures for the benefit of his people, Hon. Josiah T. Walls, the colored member from Florida, has the general interest of his State and nation at heart, and labors to promote them with commendable zeal. We have before us the speech of this gentleman before the Transportation Committee of the United States Senate advocating the construction of a canal through the peninsula of Florida, in which the advantages to national and international commerce, with the development of the resources of the State bordering on the Gulf are treated in a clear and able manner. When such speeches are being made, and such interest is being shown by colored men in Congress we have every reason to be proud, and to entertain high hopes for the future.”

A good deal of Walls time In Congress was spent on initiatives to support and benefit his Florida constituents. He was originally elected as an at-large congressman, thus representing the entire state. He sought funding to erect telegraph lines, courthouses and post offices. He advocated improvements to the state’s harbors and waterways and sought tariffs to protect Florida’s growers. As was the case with many of the Black Congressmen during the Reconstruction era, most of his proposals never made it out of committee and to the House floor.

Walls was originally elected as a Republican in 1870, going head to head against former slave owner and Confederate veteran Silas L. Niblack. It was during that campaign that an assassin’s bullet missed Walls by inches during a rally in Gainesville. Niblack contested the election, claiming canvassers had thrown out Democratic ballots. Walls had served most of his two-year term before the House voted in Niblack’s favor and Walls was unseated. Undeterred, he ran again in 1872 and was again elected.

Following his second term, Walls used his Congressional salary to purchase a former cotton plantation. He also bought a newspaper, the Gainesville New Era.

Seeking a third term in 1874, Walls defeated a Conservative candidate Jesse T Finley in a vote that was pretty much strictly along racial lines. Again the election was contested. Finley claimed that some votes in Walls’ home Alachua County were invalid because Florida’s eligibility oath requirement was not correctly met. With Democrats now in control of Congress, Walls was again unseated.

Back in Florida, he had some considerable success as a farmer, growing cucumbers and tomatoes. After a freeze destroyed his crops in 1895, he took a position managing the farm at Florida Normal College (later renamed Florida A&M). He died in 1905.

The next time Florida would elect a Black representative was Carrie Meek in 1992. On that occasion the Tampa Tribune (Sept. 12,1992) looked back at Walls’ career:

“He survived three hard-fought campaigns. Walls was a spirited, bare-knuckle politician, but the tide was against him. The protection afforded by Reconstruction disappeared with the return to power of disenfranchised rebels. He quit politics in 1884, after one last lively but disastrous come-back effort.

“With the collapse of Reconstruction, racial segregation and oppression thwarted black political aspirations until the Civil Rights Movement forced passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. And even with that, it has taken another 27 years for a Florida black politician to win a seat in Congress. Maybe Carrie Meek’s victory moves us a little closer to achieving the justice sought by Josiah Walls so many years ago.”

-O-

From Slavery to Capitol Hill posts:

“In the year 1865 two thirds of the city of Selma was reduced to ashes by the United States Army . The Government made a display in that unfortunate city of its mighty power and conquered a gallant and high-toned people. They may have sinned wonderfully but they suffered terribly.

“War was once the glory of her sons, but they paid the penalty of their offense, and for one, I have no coals of fiery reproach to heap upon them now. Rather would I extend the olive branch of peace, and say to them, let the past be forgotten and let us all, from every sun and every clime, of every hue and even shade, go to work peacefully to build up the shattered temples of this great and glorious Republic.”

Those were the words of Alabama’s first Black congressman, Benjamin Sterling Turner, delivered on the floor of the House of Representatives on May 30, 1872. It was part of his appeal to gain funding to rebuild Selma. The Selma Times Journal, which reprinted part of Turner’s speech (Jan. 20, 2008) described Turner as a “good man who was born into slavery, yet was not embittered by it, and lived a lifetime serving his city, state and country well.”

Reconstruction Alabama, was a bitterly divided society of radical Republicans, carpetbaggers, resentful Confederates, Klansmen and sundry other white supremacists. Turner was the most unusual of public servants, a moderate.

Turner was born in 1825 in North Carolina. His owner, a widow named Elizabeth Turner, took him with her when she moved to Selma. Ben Turner was 5 at the time. Turner learned to read and write, likely by sitting in with the family’s white children during their lessons. When he was 20, Elizabeth Turner sold him to W.H. Gee who was the husband of her stepdaughter.

Gee deployed Turner to manage his livery stables and the Gee Hotel in Selma. Turner married an enslaved woman named Independence, but she was sold to a white man who took her as a mistress. When Gee died, Turner was inherited by his brother, James Gee. Based on his experience, James Gee assigned him to manage the St. James Hotel in Selma.

Turner’s education and experience served him well after emancipation and he became a successful farmer and merchant in Selma. He also set up a school for Black children there in 1865.

Turner first ran for Congress in 1870. His home district had a 52 percent Black electorate. He financed his campaign by selling a horse. His platform: universal suffrage and universal amnesty. He ended up winning 58 percent of the vote, defeating Democrat Samuel J. Cummings.

Turner only had two years in Congress. He spent it tirelessly advocating for the people in his district. This included: seeking repeal of a tax on cotton, urging reparations for ex-slaves, and supporting various economic revitalization bills. His appeals fell on deaf ears as Congress acted on none of these initiatives.

When he was up for re-election two years later, the Black vote was split between himself and another Black candidate, newspaper editor Philip Joseph. As a result, the Democratic candidate Frederick G. Bromberg was elected with 44 percent of the vote.

Turner returned to his businesses, but suffered serious losses during the depression of the 1870’s. He was nearly penniless when he died in 1894 and was buried in an unmarked grave.

More than 90 years later, in 1985, a group of Selma citizens, both Black and white, made donations to place a marker on Turner’s grave. The following year, at an unveiling of a portrait of Turner at the Old Depot Museum, the Montgomery Advertiser (Feb. 10, 1986), reported these comments from city leaders:

“’If John F. Kennedy had been aware of Benjamin Turner, he would have included him in ‘Profiles In Courage,’ said state Rep. W.F. ‘Noopie’ Cosby, D-Selma.

“’It’s high time his courage has been recognized,’ Selma City Council President Carl Morgan said.

“’This diverse group is more of a monument to him than the portrait,’ said state Sen. Hank Sanders, D-Selma.”

-0-

From Slavery to Capitol Hill posts:

“Darkness still blanketed the city of Charleston in the early hours of May 13, 1862, as a light breeze carried the briny scent of marshes across its quiet harbor.

“As thin wisps of smoke rose from the vessel’s smokestack high above the pilothouse, a 23-year-old enslaved man named Robert Smalls stood on the deck. In the next few hours, he and his young family would either find freedom from slavery or face certain death. Their future, he knew, now depended largely on his courage and the strength of his plan.

“At about 4:15 a.m., the Planter finally neared the formidable Fort Sumter, whose massive walls towered ominously about 50 feet above the water. Those on board the Planter were terrified. The only one not outwardly affected by fear was Smalls. ‘When we drew near the fort every man but Robert Smalls felt his knees giving way and the women began crying and praying again,’ Gourdine said. (Alfred Gouirdine one of the six other enslaved crew members.)

“As the Planter approached the fort, Smalls…pulled the whistle cord, offering ‘two long blows and a short one.’ It was the Confederate signal required to pass, which Smalls knew from earlier trips as a member of the Planter’s crew.

“With steam and smoke belching from her stacks and her paddle wheels churning through the dark water, the steamer headed straight toward the closest of the Union ships, while her crew rushed to take down the Confederate and South Carolina flags and hoist a white bedsheet to signal surrender.

“…(when) those on board the Planter realized they had actually made it to a Union ship. Some of the men began jumping, dancing, and shouting in an impromptu celebration, while others turned toward Fort Sumter and cursed it. All 16 were free from slavery for the first time in their lives.”

That story of how Robert Smalls stole a Confederate transport, freed himself and six other enslaved crew members and their families appeared in Smithsonian Magazine on June 13, 2017 (The Thrilling Tale of How Robert Smalls Seized a Confederate Ship and Sailed it to Freedom.)

When describing the accomplishments of Robert Smalls, it’s hard to know where to begin. There’s this daring escape and his later record as a naval war hero for the Union. He is seen as one of the key influences that convinced Lincoln to enlist Black men in the Union army. He led one of the first boycotts of segregated public transportation, an action that led to a city law in Philadelphia that integrated streetcars. He purchased the house of the man who had owned him as a slave. He created a school for black children in his home town of Beaufort, S.C., and started a newspaper in Beaufort. He also served a nearly unprecedented, for 19th century Black congressmen, five terms in the House of Representatives.

Smalls was born in Beaufort in 1839 to a slave mother, Lydia Polite. His father is unknown. Smalls was owned by John McKee and worked in his house. McKee later moved to Charleston and hired Smalls out on the waterfront. He progressively held jobs as a lamplighter, stevedore foreman, sail maker, rigger and sailor. He married Hannah Jones in 1856. She was an enslaved hotel maid in Charleston. They had two children, a daughter named Elizabeth and a son, Robert Jr. It was out of fear that his family members would be sold and separated that he hatched his escape plant. Hannah, Elizabeth and Robert Jr. were on the Planter when Smalls sailed it to freedom. He had become an expert in navigating the waters around Charleston and along the coast. With the start of the civil war he was conscripted into the Confederate Army and stationed on the Planter, a ship that was being used to transport munitions. After Smalls escape he continued to work on the Planter which was repurposed as a Union troop transport.

Smalls’ war record was one of the advantages he brought into his political career. Another was his ability to speak Gullah, a dialect common in the South Carolina lowlands. Like many other Black legislators at the time, he benefited from a redistricting effort that clumped Black voters into a single district, in this case Smalls hometown of Beaufort was part of a southeast coastal district with a 68 percent Black constituency. In his first bid for a house seat, in 1874, he won with 80 percent of the vote.

Smalls’ legislative record is marked by support of numerous civil rights issues as well as working to provide benefits for his coastal Caroline constituency. Most of the 19th century Black congressmen saw their Congressional representation limited to a single term, usually because of the voter suppression efforts of white supremacists. Smalls faced threatened violence, redistricting, voter intimidation and various legal maneuvers intended to unseat him, something that makes his five-term longevity all the more remarkable.

1876 saw the Democrats regain control of South Carolina, but Smalls still won reelection, defeating Democrat George Tillman with 52 percent of the vote. Having been unable to upend Smalls at the polls, the Democratic state government brought charges against him of accepting a $5,000 bribe while he had been a state senator. He was sentenced to three years, but released after three days while the conviction was appealed. He ended up being pardoned by Democratic Governor William Simpson in 1879 as part of a deal that involved dropping election law violations by Democrats.

The conviction was an electoral liability and in 1878, with voter intimidation now widespread in his district, he lost to Tillman. He lost again to Tillman in 1880 but contested the election, claiming his voters had been frightened away at the polls. The issue came before the full House, and with Democrats boycotting the vote, those present voted 141-1 to seat Smalls. In 1882, he failed to gain the Republican nomination, but the man who did, Edmund Mackey, died shortly after winning the general election and Smalls won a special election to regain his seat. He would be reelected one more time, in 1884, easily outpolling Democrat William Elliot.

After Smalls left the House of Representative in 1887, there would not be another Black congressman from South Carolina until 2011.

Andrew Billingsly, author of Yearning to Breathe Free: Andrew Smalls of South Carolina and His Families, said of the former congressman, “Robert Smalls is one of the greatest heroes of his generation. He left a legacy of service and he was the undisputed political, economic and social leader of Beaufort County for half a century after the war.” (The Times and Democrat, Orangeburg, S.C., March 16, 1997).

Smalls was 75 when he died from malaria and diabetes in 1915. On the monument in the churchyard of the Tabernacle Baptist Church in Beaufort where he is buried, there is an inscription of one of his quotes from the floor of the South Carolina legislature: “My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

-0-

From Slavery to Capitol Hill posts:

George Washington Murray was the only Black man in Congress when he served two terms in the House of Representatives from 1893 to 1897. The other Black legislators that I’ve highlighted in this series served terms in the 1870’s and 1880’s. By the time Murray was elected, suppression of the Black vote had largely succeeded in most of the South to disenfranchise the Black population. Murray spent most of his career fighting those efforts.

The Boston Public Library has a handwritten letter, dated April 5, 1877, from Murray to the journalist and noted abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison in which he describes the situation in the southern states. He says, “”my people have been driven from their own homes by the fierce assassins in their midnight raids, and in many cases they have been brutally murdered…died martyrs for the cause of their principle and liberty.” He also talks about “one Colonel Ferguson,” from Mississippi, who Murray claims canvassed the state prior to the election forming “Sabre, Rifle and Artillery Clubs” to terrorize and suppress African-American and Republican voters.

Murray was born into slavery in Sumter County, S.C. His parents are unknown. While receiving no formal education as a child, he taught himself to read and write. In 1874 he enrolled in the University of South Carolina, which had been opened to Black students by the Reconstruction government. In 1877, after federal troops had left the south and with white Democrats in control of the state legislature, the Black students were expelled. Murray completed his education at the historically black State Normal Institution at Columbia.

As a free man, Murray worked as a farmer and a teacher. He held seven patents for farm equipment he invented. His inventions included an automatic cotton chopper and a fertilizer distributor.

Murray’s electoral history shows what it was like for a Black man to seek election in the South. In his first attempt to gain the Republican nomination for a House seat in 1890, he ran in what was known as South Carolina’s “shoestring district,” which included Charleston. As in many of the other southern states, South Carolina had gerrymandered a district to include most of the Black vote, thereby diluting its influence in the other districts. He lost to the incumbent, Charles Miller, who was also Black. Miller lost the general election to Democrat William Elliot.

In 1892, Murray tried again. After winning the Republican nomination he faced the Democrat E.M Moise in the general election. There were numerous reports of votes for Murray being thrown out for trivial reasons. Ballots a sixteenth of an inch too short were discarded as were some in which the precinct manager failed to include the precinct number. Mosie was declared the winner. But Moise had been at odds with the controlling group of Democrats and when the results came before the board of elections, they declared that Murray had won by 40 votes.

In his reelection bid in 1894, Murray had to run in a different district as the Democratic legislature had broken up the old “shoestring district.” Again his opponent, this time it was former rep William Elliott, was initially declared the winner. Murray again appealed and when he got nowhere at the state level, took his case to the House in Washington. Among the evidence Murray brought: ballot boxes in three predominantly Republican counties were never opened and in some black precincts, the polls never opened. There were also reports of Elliott himself standing in front of ballot boxes intimidating black voters. The House voted to seat Murray, by a 153-33 vote. By the time Murray sought reelection again in 1896, South Carolina Democrats had amended the state constitution and at the polling locations that meant residency requirements, literacy tests, poll taxes and property requirements. This time, Elliott got 67 percent of the vote. When Murray left Congress in 1897, there would not be another Black representative from South Carolina for 100 years.

A syndicated wire service report on election fraud that I found in the Chadron Record of Chadron, Neb., on March 5, 1897, had this to say: “In the seven extreme Southern States, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas and Louisiana, the population in 1890 was 3,306,465 greater than in 1870 yet the vote of 1896 was 195,003 less than In 1876. George Washington Murray is entitled to the respect and thanks of every patriotic citizen irrespective of race, color or previous condition of servitude for calling attention to these facts.”

On the house floor, a good deal of Murray’s time was spent trying to fight off the voter suppression efforts of white supremacists. In 1893, Virginia Representative Henry Tucker introduced a bill calling for the removal of federal marshals and impartial election supervisors. Murray took the floor, “While I can not persuade myself that there can be found here and in the Senate enough cruel and wicked men to make this law effective, still if I am disappointed in that…I hope that the broad–souled and philanthropic man occupying the Executive chair is too brave and humane to join in this cowardly onslaught to strike down the walls impaling the last vestige of liberty to a helpless class of people.” Congress passed the bill and President Grover Cleveland signed it.

The Yorkville Enquirer, York, S.C., April 24, 1895, reported on Murray’s appeal in that town: “Ex-Congressman George Washington Murray, colored, was in Yorkville last Thursday night, and delivered an address to a large assemblage of colored people in the Wesleyan M. E. church. The object of his visit was to secure contributions toward a fund of $2,000 which his people are trying to raise for the purpose of pushing the fight that has already been inaugurated against the registration laws of this State. He claimed that his people had no desire to rule this State again; but, at the same time, there can be no doubt of the fact that it is of the utmost importance to them that they shall retain their voice in the election of their representatives and other public officers. He made quite an impression on his hearers, and succeeded not only in raising a small subscription on the spot; but also in organizing committees to make still further collections.”

His time in Congress done, Murray returned to farming. By the turn of the century, he had amassed some substantial amount of farmland in his home county. He leased that land in small plots to farmers to grow cotton. At one time there were some 200 farmers working plots leased by Murray, After two of his tenants brought him to court over a contract dispute, he was convicted of forgery and sentenced to three years. Rather than turn himself in, Murray fled to Chicago. A later South Caroline governor, Coleman Blease, pardoned him in 1915.

Murray spent his later years delivering lectures on race relations around the country. His speeches were consolidated into two books: Race Ideals: Effects, Cause and Remedy for Afro–American Race Troubles (1914) and Light in Dark Places (1925). He died of a stroke at home in 1926.

-0-

From Slavery to Capitol Hill posts:

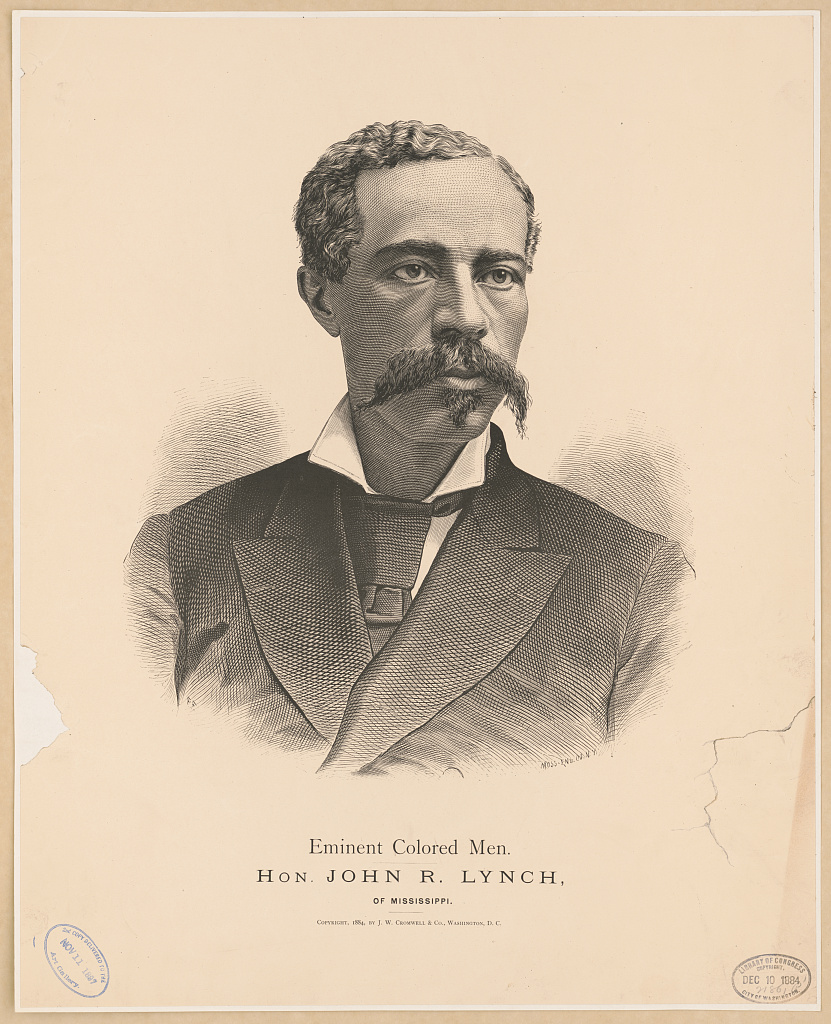

John Roy Lynch wasn’t just the only Black man to represent Mississippi in Congress for more than a century. He was a veteran who rose to major in the Army, a lawyer, a successful businessman and an author. And this is a guy who started life as a slave.

Lynch was born on the Tacony Plantation in Vidalia, Louisiana, in 1847. His father, an Irish immigrant named Patrick Lynch, worked as an overseer on the plantation. His mother, Catherine White, was a mixed-race slave. She was Patrick’s common law wife, interracial marriage being illegal at the time. Patrick tried to keep the family together and had a plan to buy Catherine, John and his two brothers and free them, but he died before achieving that goal. After his death, the family was sold to Arthur Vidal Davis, a Natchez, Miss., planter. Davis agreed to keep the family together, Catherine worked in the household, John in the fields. They were liberated in 1863 after the Emancipation Proclamation. John was 16 at the time.

Lynch would go on to serve three terms in Congress. He was elected from a coastal Mississippi district that included Natchez. At the time of his first election in 1873, the district was 55% Black. Along the way in his political career Lynch achieved a number of firsts. He was elected to the state house of representatives in 1869 and in 1872 he was chosen to be speaker of the house, the first Black man to hold that position in any state. He was 25 at the time. When he took his seat in the 43rd Congress in 1873 he was, at 26, the youngest member of the House. Several years later, in 1884, he was a delegate to the Republican National Convention and delivered a keynote address, the first African-American to do so.

As a legislator, Lynch focused mostly on economic issues aimed at helping his constituents. He sought funding for an orphanage damaged during the Civil War, he sponsored legislation seeking reimbursement for depositors who lost money due to the failure of the Freedmen’s Savings and Trust Company and sought funding to improve the Mississippi River shoreline. He was a member of the Committee on Mines and the Committee on Expenditures.

He also was an avid supporter of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 which prohibited discrimination in public places, including public transportation and restrooms. Following is an excerpt from a speech Lynch made on the House floor supporting that legislation:

“I am treated, not as an American citizen, but as a brute. Forced to occupy a filthy smoking-car both night and day, with drunkards, gamblers, and criminals; and for what? Not that I am unable or unwilling to pay my way; not that I am obnoxious in my personal appearance or disrespectful in my conduct; but simply because I happen to be of a darker complexion… Mr. Speaker, if this unjust discrimination is to be longer tolerated by the American people, which I do not, cannot, and will not believe until I am forced to do so, then I can only say with sorrow and regret that our boasted civilization is a fraud; our republican institutions a failure; our social system a disgrace; and our religion a complete hypocrisy.”

Lynch’s military service started right after he was emancipated. During the civil war he served as a cook for the 49th Illinois Volunteer regiment. Thirty some years later, during the Spanish-American War, he was commissioned a major in the Army and appointed paymaster by President McKinley. He served in both Cuba and the Philippines.

In between his stints in Congress and his military gigs, Lynch at one time ran a successful photography business. He was admitted to the bar in Mississippi and practiced law.

Later in life, this man who at one time had sought to further his education by eavesdropping near a open window at the white school in Natchez, turned to writing. His most notable work was The Facts of Reconstruction, published in 1913. It was written in response to some works by white historians that negatively portrayed the role of the Black Republicans after the Civil War. He was a contributor to the Journal of Negro History and when he died he was working on his autobiography. Reminiscences of an Active Life: The Autobiography of John Roy Lynch was eventually published in 1970. A new edition was published by the University of Mississippi Press in 2007.

In 1974 a street in Jackson, Miss., was named after Lynch. On that occasion (May 3, 1974) the Jackson Clarion Ledger had this to say: “Lynch was elected to the legislature at the youthful age of 22, and was elected speaker at 25. In 1873, his colleagues presented him with a gold watch and chain. A prominent white Democrat proposed a resolution thanking Lynch for his ‘dignity, impartiality, and courtesy.’ In 1880, the Jackson Clarion referred to him as, ‘the ablest man of his race in the South.’”

-0-

From Slavery to Capitol Hill posts:

John Adams Hyman was the first Black to represent North Carolina in the U.S. House of Representatives. But perhaps the most impressive part of Hyman’s career is what he went through to educate himself.

Hyman was born into slavery in Warrenton, N.C., in 1840. At the time, nothing struck fear in the hearts of Southern slaveholders more than the prospect of an educated slave. While it was illegal throughout the southern states to educate slaves, Hyman took it upon himself to learn to read and write. He got a little help from a jeweler named King for whom he was working as a janitor. King, being from Pennsylvania, wasn’t quite up to the repressive ways of the South, and helped Hyman out, including giving him a spelling book. When that was discovered, Hyman’s owner was forced to sell him to a slaveholder in Alabama.

That set off a continuing chain whereby Hyman, largely because of his continuing efforts to learn to read and write, was sold at least eight times during his 25 years of slavery. When emancipation came in 1865, Hyman headed back to Warrenton and enrolled in a school where he got an elementary education.

Now freed and literate, it didn’t take long for Hyman to get involved in politics. In 1867, he was a delegate at the Republican State Convention and later that year was elected to the Warren County delegation to the North Carolina Constitutional Convention. In 1868, he was elected to the North Carolina Senate, where he would serve for six years.

In 1872, Hyman ran an unsuccessful campaign to win the Republican nomination for a seat in the House of Representatives in the second district. He lost out to the incumbent Clarence Thomas. The district that included Hyman’s hometown of Warrenton was known as the “Black Second.” The state Democrats had gerrymandered the legislative map for the state in order to concentrate a large proportion of the black vote in the second district, thus rendering neighboring districts safely Democratic, and white. Hyman tried again in 1874 and this time he prevailed on the 29th ballot at the nominating convention. In the election, he defeated the Democratic candidate, George W. Blount, winning 62 percent of the vote.

Hyman’s term in the legislature was undistinguished. The Pittsburgh Courier, a weekly African-American newspaper, had this description of Hyman’s experience in Congress (May 14, 1949): “The Forty-fourth Congress was Democratic, and Hyman received only an obscure appointment on the Manufactures Committee. He submitted several measures that were of importance to the state as a whole, including one to provide a new courthouse for Jones County in place of the one destroyed by Union troops, and a bill to erect a lighthouse on Pimlico Sound. Like many other colored Congressmen, Hyman was interested in the lot of the Indians, and he introduced a measure to provide relief for the Western Cherokees. So biased was the political complexion of the House that none of these proposals even came to a vote.”

By 1876, whites had taken control of the state Republican Party and Hyman lost out on the nomination to run for re-election to a former state Reconstruction Governor Curtis Brogden.

Throughout his political career, Hyman was hounded by insinuations of corruption. It started while he was a member of the state senate, what was apparently a pretty corrupt place. There was talk he was involved in some payoffs involving the location of a penitentiary, that he took money from lobbyists during what would become a railroad bond scandal and that he accepted payment in return for endorsing a congressional candidate. Hyman was never formally charged with any of these irregularities. But the hints of corruption were used by his political opponents.

The Southern Home, a short-lived Democratic newspaper based in Charlotte, published this piece of invective on Aug. 14, 1876: “John Adams Hyman, a negro congressman from fhe 2nd District of North Carolina has developed a desire to get possession of other people’s wealth without rendering an equivalent therefor. He will retire from Congress and become a candidate for the North Carolina penitentiary.”

Not long after, he was expelled from the Warrenton Colored Methodist Church, where he was a steward and Sunday school superintendent, as a result of charges that he embezzled Sunday school funds.

He attempted again in 1878 and then again in 1888 to gain the Republican nomination for the Congressional seat, but was defeated. The following year he moved north to Washington, D.C., where he got a job with the Department of Agriculture. He passed away in 1891 after suffering from a stroke in his home.

-0-

Other From Slavery to Capitol Hill posts:

For some 200+ years, from 1776 until 1992, the state of Georgia had one Black representative in Congress. And that one was only there for a term of less than three months. But Jefferson Franklin Long didn’t fail to make his mark during his short time. He is credited with being the first Black representative to make a speech on the House floor.

The occasion, in 1871, was a proposed bill to grant amnesty to former Confederates. Long was not a supporter. Here’s what he had to say:

“Do we, then, really propose here today, when the country is not ready for it, when those disloyal people still hate this government, when loyal men dare not carry the ‘stars and stripes’ through our streets, for if they do they will be turned out of employment, to relieve from political disability the very men who have committed these Kuklux outrages? I think that I am doing my duty to my constituents and my duty to my country when I vote against any such proposition… Mr. Speaker, I propose, as a man raised as a slave, my mother a slave before me, and my ancestry slaves as far back as I can trace them… If this House removes the disabilities of disloyal men by modifying the test-oath, I venture to prophesy you will again have trouble from the very same men who gave you trouble before.”

Long was born in 1836 to a slave mother in Knoxville, Ga. He was the property of a tailor named James C. Lloyd, who was likely his biological father. Although it was illegal at the time, he taught himself to read and write. Lloyd moved to Macon where he sold Long to Edwin Saulsbury, a local businessman. Saulsbury set Long up in a tailor shop in Macon. The historical records aren’t clear as to whether Saulsbury freed Long before emancipation in 1865, but as a free man, Long operated a successful tailor business. Most of his customers were white as they were the only people who could afford custom-made clothes.

Long’s interactions with his customers led him into politics. He had been active promoting literacy for African-Americans through an organization called the Georgia Educational Association. He was a strong supporter of the Republican Party and actively campaigned to promote the party to Black Georgians.

Following the Civil War, Georgia was not immediately granted re-admission to the Union because the state legislature refused to ratify the 15th amendment establishing the right to vote irregardless of race. It was not until 1870, after ratifying that amendment and reinstating an elected group of black state legislators who had been expelled, that Georgia once again became part of the United States.

That set up an unusual election in which the state at the same time elected representatives to fill the term of the 44th Congress (1869-1871) as well as representatives for the full-term 45th Congress (1871-1873). The Republican Party offered up white candidates for the full-term positions and Black candidates for the short terms. Long was one of the latter.

Long won the election with 53% of the vote against Democrat Winburn J. Lawton. After some delay, he was seated in January 1871 for a term that was to expire in March.

The other most notable part of Long’s career was his involvement in what the white press called the “Macon riots” on election day in 1872. Voter suppression efforts were now in full swing across the South, something that would eventually close the polls to Black voters. Long organized a group of Black citizens to head to the voting location in mass where they were met by a group of newly deputized and armed whites. In the ensuing melee two Blacks and one white man were killed.

The Southern white spin on this event is expressed in the following story from the New York Herald on Oct. 3, 1872:

“A fight occurred at the polls in Macon today growing out of another attempt by the negroes to take forcible possession of the polls… Very early in the morning they massed at the City Hall and marched down to the polls… There they met a smaller crowd, principally whites, and commenced crowding upon them and forcing them away from the polls. A few bouts of fisticuffs occurred in the dense mass, and then a discharge of brickbats came from the negroes, followed by an order from their leader, Jeff Long, to fire upon the whites. In the course of a few seconds about fifty pistol shots were discharged from both sides by which one white man was killed and some five or six negroes wounded, two of whom have since died.”

The Boston Globe of Oct. 21, 1872, offers a different take. It quotes a local Greeley Club president as declaring that the riot was “the work of white men, and they had no provocation.” On Long’s involvement:

“Jeff Long, colored, ex-member of Congress from that district, made a speech on the same evening, in which he replied to the charge that he advised his people to arm themselves, and showed that, on the contrary he had urged them; to go to the polls without even a cane, because he really trusted to the good conduct of the whites. Long has been criticized on both sides – charged with provoking violence by the Democrats, and by his own people with so advising them as to leave them helpless.”

Long came out of this unscathed, but backing away from politics. His reputation among whites in Macon took a hit and that impacted his tailoring business so he branched out into dry cleaning and liquor sales. He remained a self-employed Macon resident until his death in 1901.

In an ariticle in the Winter 2011 Georgia Historical Quarterly, titled Incendiary Negro: The Life and Times of the Honorable Jefferson Franklin Long, the author, Ephraim Samuel Rosenbaum, summed up Long’s career as follows:

“Given the oppressive social and political conditions in which he was compelled to operate, Long’s accomplishments were remarkable. He was a slave-born tailor who rose to the top of his party and maintained the loyalty and admiration of the majority of its members over the course of nearly fifty turbulent years, this despite the fact that the party had effectively abandoned his race and state.”

-0-

From Slavery to Capitol Hill posts:

“A kinder country would have embraced him as everything America dreams of. A survivor of the physical and spiritual torture of the nation’s gravest sin, Haralson had the bravery to defy his former tormentors, teaching himself how to read and write and using his natural gifts to go from chattel slavery to the halls of Congress in a little over a decade. Haralson completed his term in Congress a month before his 31st birthday.”

Those are the words of Bryan Lyman writing in the Montgomery Advertiser on Feb. 26, 2020 (The Lost Congressman: Whatever Happened to Jeremiah Haralson?).

Jeremiah Haralson was born into slavery near Columbus, Ga., in 1846. No one knows for sure where he died or when. In between, he was Alabama’s first Black man elected to the state House of Representatives and one of the first black Congressmen who took their seats on Capitol Hill during Reconstruction.

Haralson was his own man. He at times supported Democrats as well as Republicans. And he was not afraid to take unpopular stances, like supporting a bill to grant amnesty to Confederates.

Haralson started life as a slave in Georgia. After his owner died he was sold at least twice. Little is known of his parents or at what point he was separated from his family. In 1859, he was sold to a Selma, Ala., lawyer named John Haralson. He was emancipated in 1865 after the Civil War and the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery.

As a free man, Haralson taught himself to read and write. His entry into politics was a result of his skill as an orator. He is first seen in politics in 1868, campaigning for Horatio Seymour, the Democratic presidential candidate who ran against Ulysses S. Grant. The unusual choice for a Black man to support the party of former slaveholders and Confederates was explained by Haralson as a result of loyalty to his former owner. He later disavowed the sincerity of his support for Seymour, saying he had simply been paid to write speeches and that in private he urged people to vote for Grant.

In 1870, when Haralson successfully ran for a seat on the state House of Representatives, he was a Republican. Two years later, he was elected to the Alabama Senate. It is in that position that he achieved his greatest success as a legislator. He pushed through the passage of a bill requiring equal funding of schools and was also sponsor of a civil rights bill that required transportation and hospitality services to provide equal accommodations.

In 1874 Haralson ran for the U.S. House of Representatives in a district that was 50 percent Black. In that election, he defeated Frederick Bromberg, the Liberal Republican incumbent. Haralson had 54 percent of the vote. Despite his skills as an orator, Haralson never made a speech on the house floor. It was during this lone two-year term that he controversially voted in favor of an amnesty bill for Confederates. His explanation: ““The colored man in the South wants peace and good will to all and hatred to none, and asks for others what he desires for himself — an equal chance in the race of life. We, as a race, cannot afford to aid in any manner in keeping up strife for the benefit of office-hunters.”

Haralson failed in two attempts to be re-elected, a result of divisions within the Republican Party and the growing efforts of white southern Democrats that would eventually disenfranchise Blacks in Alabama and elsewhere in the South. In 1876 he lost a three-way contest with former Black Representative James Rapier and the Selma sheriff, Democrat and former Confederate Charles M. Shelley. With Haralson and Rapier splitting the black vote, Shelley was able to win with 38 percent of the vote. Numerous irregularities were reported but Haralson’s mostly illiterate poll watchers were intimidated and powerless.

After Haralson left office in 1877, there would not be another Black Alabaman in the House of Representatives until 1992.

Following his electoral defeats, Haralson moved to Washington where he got some patronage jobs from the Grant administration. In 1894, he was in Arkansas working as a pension agent when he was arrested and charged with pension fraud. The jury deliberated for 15 minutes and the judge threw the book at him, two years, maximum sentence. The last public record of Haralson is of him entering Albany (N.Y.) County Penitentiary in 1895.

Haralson’s official Congressional biography states that he eventually moved West, landing in Colorado where he worked as a coal miner and was killed by a wild animal while hunting. There is no death certificate, no known grave and nothing to corroborate that story.

Lyman concludes, “Haralson faded like a half-remembered dream. The nation forgot, as it forgot the pain and triumph of so many African-Americans.”

-0-

From Slavery to Capitol Hill posts: