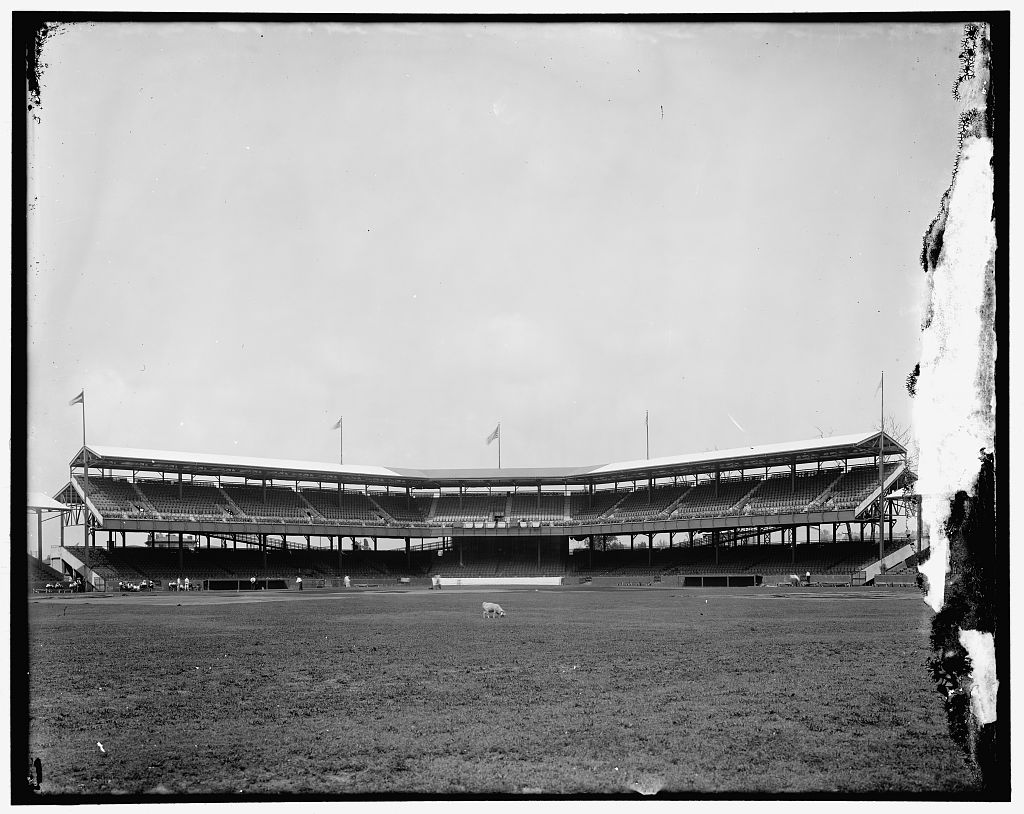

The Chattanooga Lookouts, a Double-A affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds, got their name in 1909 after a fan contest resulted in naming the team after nearby Lookout Mountain. The Lookouts have played in four different leagues, have been affiliated with seven different major league teams in addition to the Reds. They have called three different ballparks their home, Andrews Field, Engel Stadium (opened in 1930) and the current AT&T Field (opened in 2000).

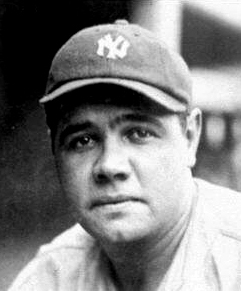

The Lookouts have won seven Southern League division titles and three league championships, the most recent being in 2017. But the most famous night in Lookout history occurred during a pre-season exhibition game on April 2, 1931. That was the night when a 17-year-old local girl who signed with the minor league team as a way to earn money for college pitched in an exhibition game against the New York Yankees. Jackie Mitchell only faced three batters. The first two were Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. Both struckout.

Baseball historians will scratch their heads over whether to take this seriously. There is no doubt that it happened. Here’s how it was described the next day in the Chattanooga Daily Times:

“Jackie Mitchell hied (sic) herself to the hill, while the crowd arose with deafening applause. Babe Ruth, the Bambino himself, was at the plate. After warming up, Jackie shot one over with all disdain for the mighty slugger, but it was inside and was called a ball. While most girls would have been so excited that they would have thrown the ball in the stands, Jackie was 4 degrees cooler than the proverbial cucumber.

“Second pitch came with a quick hop and the Babe swung and missed. Another ball, then Babe cut under another. Babe waited, looking for another inside and Jackie breezed one straight through the middle. A perfect strike. Babe threw down his bat in disgust and stalked into the dugout.

“Lou Gehrig did the same thing except different. He went down swinging.”

MItchell walked the third batter she faced, then was pulled from the game.

MItchell herself wrote the following description of the fateful strike three for the United News: “I thought he would look for another one close and high, so I threw the next one straight down the alley with all the smoke I could put on it. The Babe let this one go, but the umpire called it for the third strike. Mr. Ruth was pretty mad, but I am sure he was mad at the umpire and not me.” (Pittsburgh Post Gazette, April 4, 1931).

While Chattanoogans were likely pretty proud of their local hero. They weren’t buying it in Brooklyn.

“Jackie Mitchell has struck out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig and now she can go home and tend to her knitting.

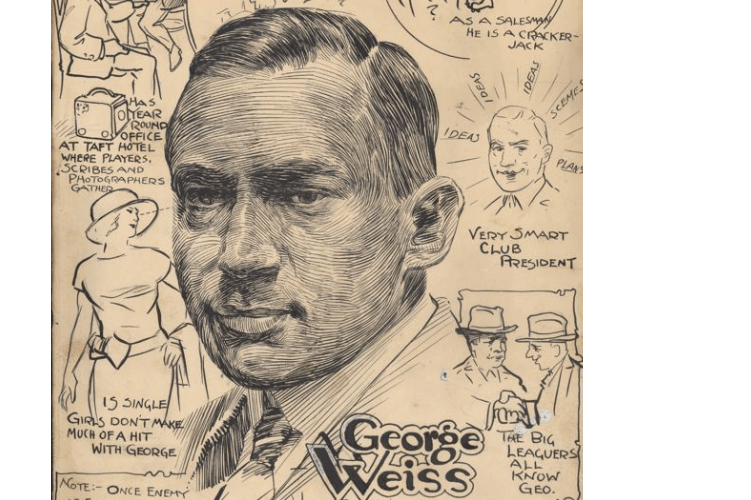

“The 17-year-old girl pitcher who so impressed Joe Engel, president of the Chattanooga Lookouts of the Southern Association, that he signed her up for his ball team, was given her chance against the Yankees here yesterday and she ‘made good,’ with a little assistance from the Messrs. Ruth and Gehrig.

“Ruth did his act perfectly, calling for an examination of the ball after he ‘struck out.’ For this fine piece of showmanship he was given a Chattanooga version of the Bronx cheer.” (Brooklyn Times Union, April 3, 1931)

And there was no shortage of snide comments. This one came in a column called “Fodder for Sports from the Press Box” in the Bluefield (W.Va.) Daily Telegraph. “They tell me you may as well forget Miss Jackie Mitchell, the woman pitcher of Chattanooga, as far as pitching is concerned. She couldn’t throw a ball hard enough for a hop, nor spin it enough for a curve. It takes curves to pitch baseball and Jackie’s aren’t that kind.” Probably best for the author that there is no byline on this story.

A couple weeks after the Yankee game, Engel, a guy who once traded his shortstop for a 25-lb. turkey, had second thoughts. He announced that Mitchell would not be accompanying the team on their season-opening road trip and that perhaps she would be in a position to contribute further next year. There was no next year as Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis, the racist commissioner of baseball known for keeping the game segregated, voided Mitchell’s contract, suggesting that women weren’t tough enough to play baseball. In an interview with the St. Louis Post Dispatch, Mitchell commented, “I believe I could qualify and might be signed by a major league team and might someday get to play in a World Series if Judge Landis hadn’t ruled against my playing in major league ball. He doesn’t give any reason for his ruling either.”

But there was also a lot of publicity and a lot of people bought tickets. Recognizing this the Joplin Miners of the Western Association signed a female catcher Vada Corbus, though it seems that Corbus never actually took the field for the Miners.

Mitchell went on to have a successful season for the Chattanooga Junior Lookouts, drawing crowds wherever she played. Later she joined the barnstorming House of David team.

As for the Lookouts, they finished the 1931 season 79-74. The following year they won the Southern Association championship with a record of 98-51. They then won the only Dixie Series title in their history beating the Beaumont Explorers of the Texas League four games to two.

Joe Engel remained with the Lookouts for 34 years and in 1960 was presented the ‘King of Baseball’ award by Minor League Baseball.

Sadly the Lookouts, despite their long and storied history, are rumored to be on the MLB’s list of minor league teams that will be cut before the 2021 season.

-0-

Other History of the Minors posts: