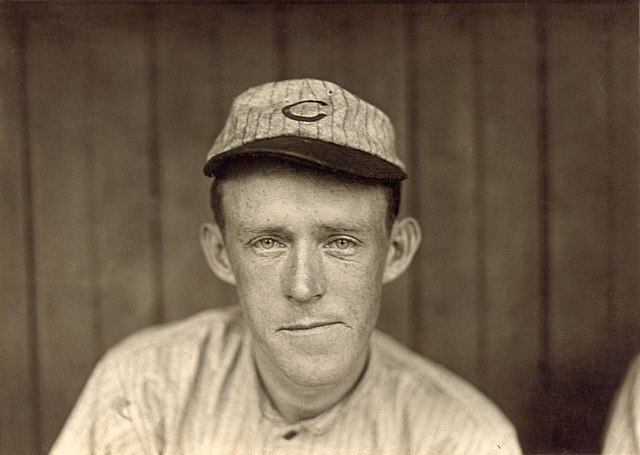

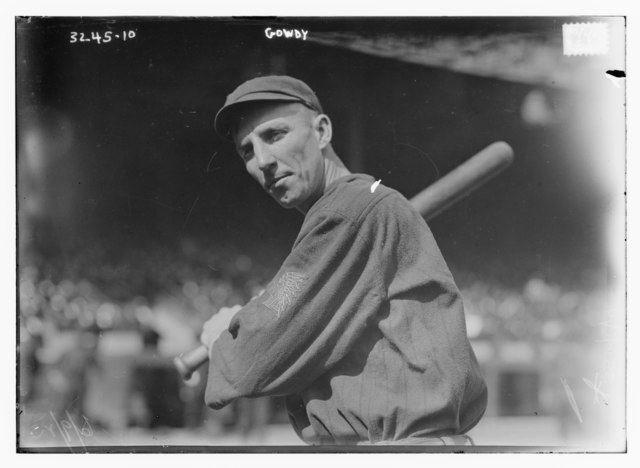

There are no doubt some really dumb baseball plays that have been made by undistinguished players in meaningless games between mediocre teams. Those plays are neither remembered nor recorded. But a gaffe in the deciding game of a World Series takes a long time to forget. That was the fate of Hank Gowdy.

Gowdy not only had a distinguished 17-year major league baseball career, but he was a war hero that participated in two world wars. Perhaps his finest moment as a ballplayer came during the 1914 season with the Boston Braves. It was Gowdy’s first year as a regular major league catcher. This was a team that was christened the “Miracle Braves,” a team that came back from more than 20 games behind in July to overtake the more fancied New York Giants and find their way into the 1914 World Series against the Philadelphia Athletics.

It was during that series that Gowdy became the first slugger to earn the nickname “Hammering Hank.” He batted an amazing .545 for the series and in game four, he went 3-for-4 to lead the Braves to a sweep.

Three years later, Gowdy would be doing a different kind of hammering. In 1917 he was the first active major league ballplayer to enlist. He joined the Ohio National Guard and was sent to France. There he fought on the Western Front, active in the brutal trench warfare that was so much a tragic part of World War I.

Gowdy returned to the Braves after the war. He once caught an entire 26-inning game, a 1920 contest between the Braves and the Brooklyn Robins that was eventually declared a 1-1 tie.

In 1923 he was acquired by the New York Giants and a year later he would find himself once again center stage in the World Series. This time for a very different reason.

The series between the Giants and the Washington Senators was tied three games apiece with the deciding seventh game to be played Oct. 10 at Washington’s Griffith Stadium. Going into the 12th inning, the game was tied 3-3 as well. In the bottom of the 12th the Senators Muddy Ruel hit what seemed to be an easily corralled foul pop up. Gowdy, behind the plate for the Giants, threw off his mask and headed for the ball. But he stepped on his mask, struggled to disengage his foot, and the ball dropped harmlessly to the ground. Ruel then smacked a double and he would come home with the game and series deciding run.

The following day, the Pittston (Pa.) Gazette offered this account of the fateful play: “Along with all the other throbs in one of the greatest games of ball ever played .was the tragic spectacle of Hank Gowdy, the hero of the 1914 series, one of the heroes of the 1917-1918 series with the A.E F., and the most popular player in the National League, losing the series and all that dough – $2,000 each – for the Giants.

“Hank stepped into his mask, which he had hurled to the baseline when he went after Ruel’s foul in the last Inning. He kicked the thing away and then stepped into it again and stumbled, dropping the ball. Ruel, with his life at the bat prolonged by Hank’s error, doubled and came in with the run that made the master mind of that well known John McGraw look not so good some more.”

Gowdy was not one to go into hiding. The United News ran a story on Oct. 11 that Gowdy himself wrote. Here’s how he described the incident:

“I never made an alibi in my life and I’m too old to start. Yes, I dropped Ruel’s foul in the twelfth and instead of being put out Kuel came back and knocked a double which placed him in the position from which he scored the winning run. I had stumbled and was off stride when the foul got away from me. In my years I have caught several thousand fouls. I never stop to give myself three rousing cheers for catching one. But when I miss one, I feel pretty sore at myself. However, it was a 12-inning ball game and no one play decided it.”

He then showed his character by adding: “Washington won cleanly and with fine sportsmanship. I know it is customary for the loser to say that, but I say it with real sincerity.”

After that Gowdy was up and down between the minors and the majors. His big league career ended in 1930. He had a couple of coaching jobs throughout the 30’s but with America’s entry into World War II he interrupted his coaching career to enlist again. He was 53 at the time. He was assigned to Fort Benning, Ga., where he had the title of Chief Athletic Officer. The baseball diamond at Fort Benning has since been known as Hank Gowdy Field.

-0-

Baseball’s dumbest plays:

Chicago Cubs vs. New York Giants, Sept. 23, 1908

New York Giants vs. Washington Senators, Oct. 10, 1924

St. Louis Cardinals vs. New York Yankees, Oct. 10, 1926

Philadelphia Phillies vs. Pittsburgh Pirates, July 4, 1976

Arizona Diamondbacks vs. San Francisco Giants, May 27, 2003