First of all, the usual disclaimer. These books may or may not have been written or published in 2021 (most weren’t). I just happened to read them this past year. They are roughly in order, starting with the best.

Where the Crawdads Sing, Delia Owens

Where the Crawdads Sing is a love story. A crime story. A coming of age saga. A courtroom drama. And a celebration of nature. It is an emotional, engaging, amazing novel that I ripped through.

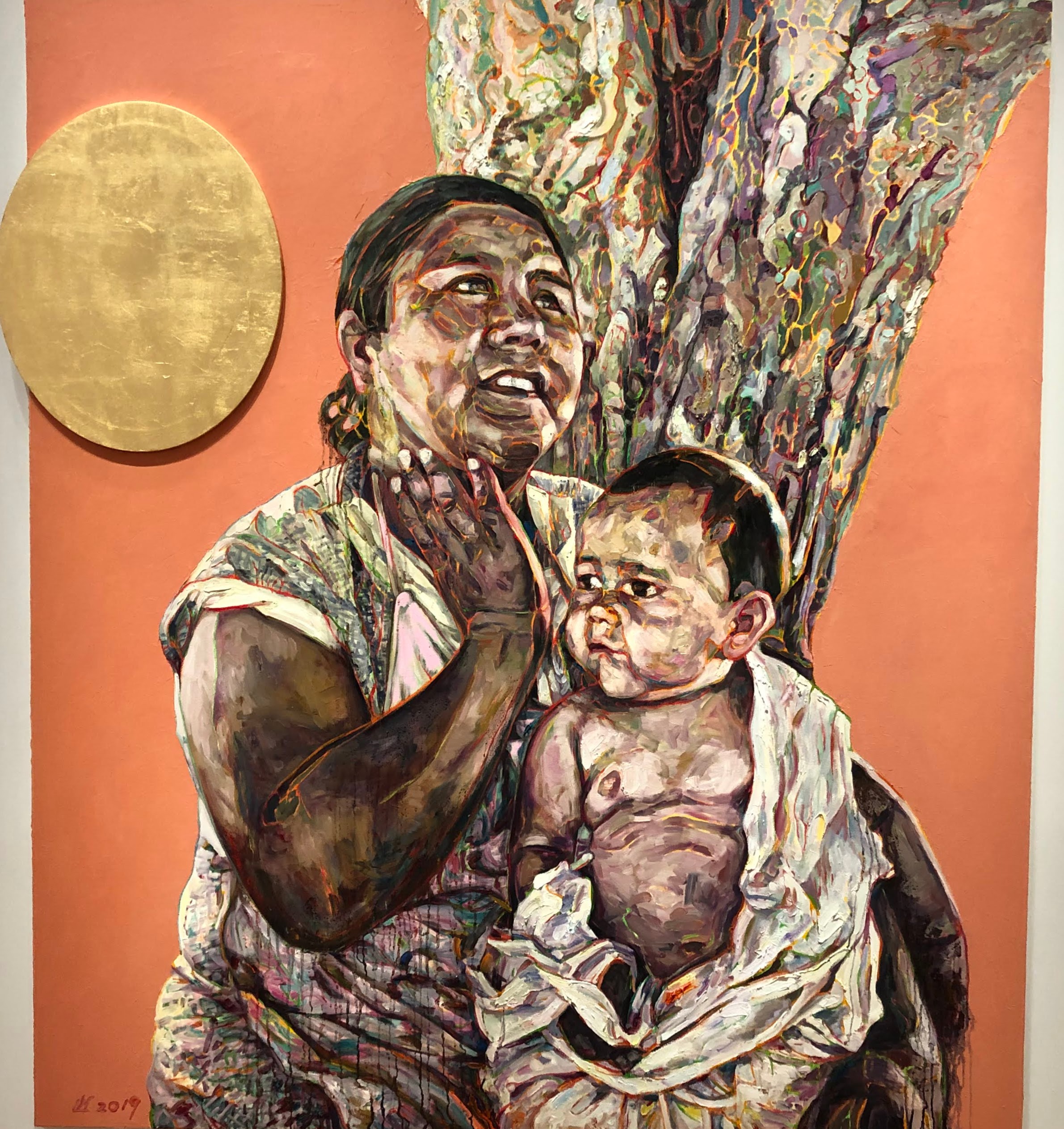

It is about the life of Kya Clark. She lives in the marshlands of North Carolina in a town called Barkley Cove. Her mother walks out on the family when she is ten. She had four siblings but they all walked as well, the result of an abusive, violent father. The old man eventually disappears as well. Kya is left to fend for herself with only a ramshackle shack and a small boat at her disposal. She collects shells and feathers, feeds the gulls, keeps herself alive by harvesting and selling muscles and stays one step ahead of the truant officer and anybody else who tries to find her in the woods.

There are other characters. Chase Andrews is at one end of the socioeconomic ladder of Barkley Cove, son of the owners of the Western Auto store and star quarterback of the high school football team. At the other end is a black man known as ‘Jumpin’ who runs the marsh equivalent of a gas station convenience store in a section of town called ‘Colored Town.’

To say too much more about the plot or the characters involved would spoil a novel that provides a surprise at every turn. There are philosophical questions the book raises about how coming together with nature affects an individual’s desire and need for human interaction.

The author has a PhD in animal behavior. She is an award-winning nature writer having previously published books about wildlife and ecology. Add brilliant novelist to her credentials.

How Beautiful We Were, Imbolo Mbue

A great novel! The story of a small African village that sits atop a reservoir of oil and how an American oil company, complicit with the local government, befouled the air, poisoned the water and laid barren the land.

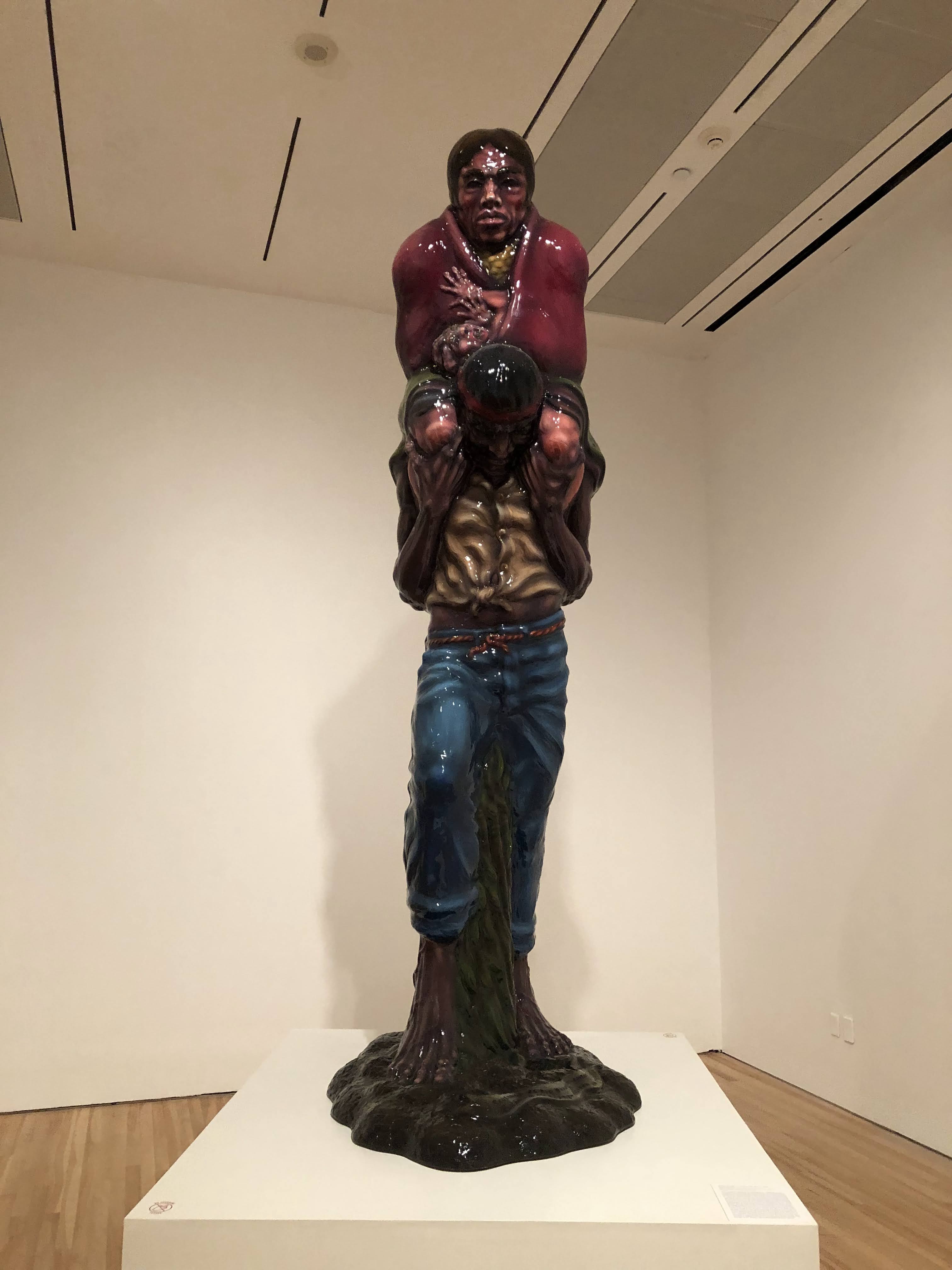

That’s not a new story but this is. It is written not just from the standpoint of the villagers but within the context of their world as they see it. This is a land where in one lifetime, slave traders came and seized them. In another lifetime, a rubber plantation enslaved them to work on their own land. And now they are free, free to watch their children die from the toxic environment.

This is a story of how they fight back. The people of the fictional land of Kosawa have no education, no resources and only machetes to face off with guns. What they have is guile and resolve. And a leader, an extraordinary woman whose life story unfolds as part of this tale.

The “we” in How Beautiful We Were is the villagers. The “were” is about a way of living with no future. Kosawa has medicine men and spirits. The villagers can seem superstitious. They can seem wise. They are indeed beautiful.

(less)

Shuggie Bain, Douglas Stuart

Shuggie Bain grows up amidst poverty, domestic violence, alcoholism, and bullying. He lives in government housing in a mine town where the mine is closing up shop. The neighborhood is so bad the neighbors ridicule Shuggie and his desperate, alcoholic mother Agnes as being posh. It’s 1980’s Scotland. You’re Celtic or Rangers. Protestant or Catholic.

If you’re looking for a story of peace, love and understanding, this is not the book for you. It is the definition of gritty. Hopelessness is another word that comes to mind. Shuggie gets routinely kicked around in the schoolyard. Agnes gets kicked around by just about every man she encounters.

There are two central themes. One is alcoholism and it’s brutal. If you think you drink too much, read this. You’ll probably quit. The other is the relationship between Shuggie and his mother. While somewhat short of heartwarming, it perseveres.

This is a terrific novel that deserves all the praise it has gotten. It is partly written in a working class Scottish dialect which helps create the atmosphere. (Children are weans, as in wee ones.) There are no heroes in this story. Just a lot of humans.

Boom Town, Sam Anderson

It’s hard to explain why I bought a book about a city that I have no connection with, had no particular interest in and that I only really expected to flyover. But I’m glad I did.

Boom Town is simultaneously a snapshot of Oklahoma City in 2013 and a history of what Anderson calls “one of the great weirdo cities of the world.” Oklahoma City was started with a “Land Run.” What’s a land run? It’s when a collection of settlers, prospectors and opportunists gather near the train tracks and, at the sound of a bugle, hustle out to lay stake to a piece of land, dry, windy and sweltering though it may be. Somehow that land run seems to explain so much of what would happen over the course of the city’s history.

Boom Town really booms and busts. Most of the booms have something to do with the oil industry. Some of the busts do too, though there’s also the grandiose and failed plans of various municipal officials, like the urban renewal project that ended up turning most of downtown into a parking lot.

There is a rich history of characters. Wayne Coyne, the lead singer of the rock band Flaming LIps, once organized a paint bucket brigade to walk through the streets of the city with leaking paint cans of every color of the rainbow. Clara Luper was a history teacher who with her 15-year old students sat in at every eating establishment in the city until, one by one, she had almost single-handedly ended segregation in Oklahoma City. For some 20 years, the town planner was a transplanted Australian who bemoaned the fact that to Oklahomans, something as simple as zoning laws was considered communism.

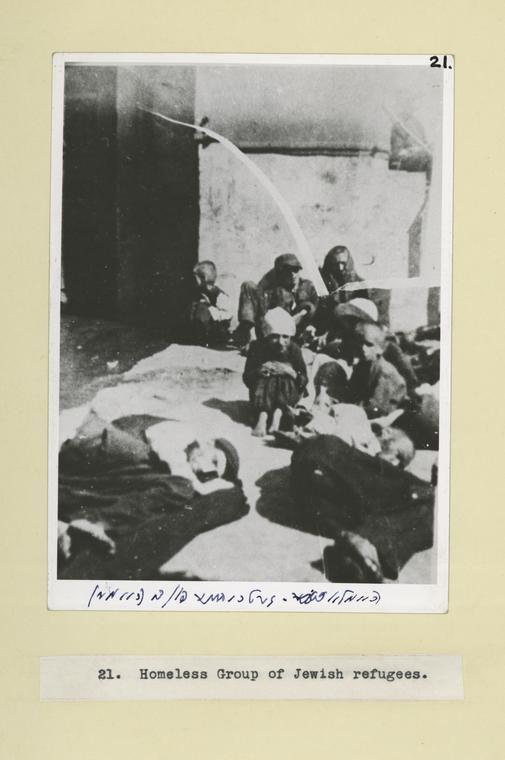

This is also a place where black soldiers heading off to World War I carried signs saying “please don’t lynch our relatives while we’re gone.”

There’s also a whole lot of basketball in this story, specifically the Oklahoma City Thunder. For a city with an inferiority complex, a city that feels a desperate need to prove it is major league, the town’s only big time professional sports team has a level of importance beyond what you will find in most places.

Anderson also has penned a stunning and heartbreaking description of the 1995 bombing of the government complex. It is not something I’ll soon forget.

“I had come to believe in Oklahoma City as a radical experiment in something– an expression of American democracy or American foolishness,” Anderson says. Whatever, this is a well-written and interesting book. You never know, I might end up booking a trip to Oklahoma City after all.

The Falcon Thief, Joshua Hammer

In May of 2010 at an airport in Birmingham, England, a janitor alerts security to a man who has been in the shower of an airport lounge for 20 minutes without ever turning the water on. Counter-terrorism officers corral Jeffrey Lendrum and when they force him to take his shirt off they find eggs rapped in socks taped to his midsection. A call goes out to Andy McWilliam of the National Wildlife Crime Unit who heads to the airport where he identifies the eggs as those of the rare and endangered peregrine falcon. Lendrum is arrested. He will be prosecuted, found guilty and jailed.

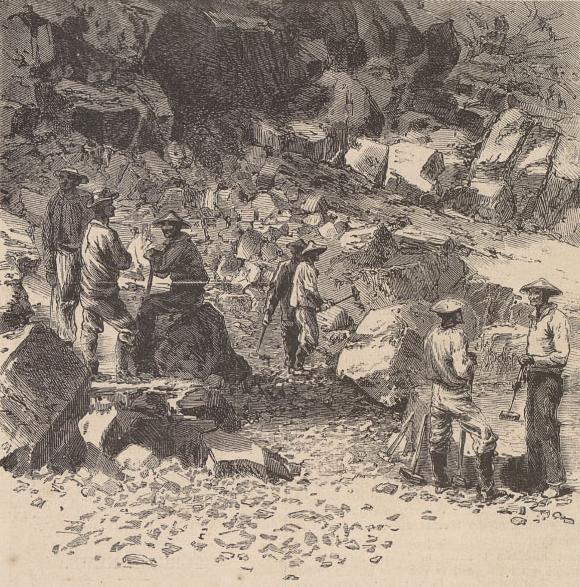

The Falcon Thief is the story of these two men and how they got to this moment. Lendrum is from a part of Zimbabwe which when he grew up was called Southern Rhodesia. Even as a boy, Lendrum was climbing trees and stealing eggs out of birds’ nests. As an adult he has a checkered career that flirted above and below the line of legality. He tried various hustles like selling aircraft parts and importing African crafts to England. But where he saw his money was in poaching the eggs of raptors. He did this in Europe, in Africa, in Canada, in Brazil. We read of his exploits in the Canadian north climbing down a rope dangling from a helicopter to reach falcon nests on the side of cliffs.

McWilliam is a career law enforcement agent. After 31 years as a cop in Merseyside, he decided to make a change and would become part of the National Wildlife Crime Unit when it was launched in 2006. McWilliam would go on to have a noteworthy career uncovering egg collectors, rhino horn robbers, badger baiters and various other enemies of wildlife.

The third part of the puzzle is more of a mystery. Who makes this a potentially lucrative venture? The money comes from rich Arab sheikhs, who at one time courted birds of prey for hunting parties, but after nearly driving the prey extinct, became obsessed instead with raptor races. Convinced that wild birds would be faster and more aggressive than any they could breed, they were the bankrollers of Lendrum and presumably others’ operations.

This is a meticulously researched story, told with enough detail to make any detective envious. It uncovers a world that most of us don’t know too much about, making it all the more interesting.

The story doesn’t really end with the Birmingham arrest. I don’t think it spoils the book to say that the aftermath of that incident suggests that this kind of egg poaching is not just an obsession but maybe even an addiction.

-0-